- 1.1 Background

- 1.2 Purpose and scope

- 1.3 Intended audience

1.1. Background

In keeping with the objectives of the Government of Canada’s ( GC ’s) Digital Government initiative, the GC continues to:

- streamline its internal and external business processes

- improve how it delivers services to Canadians

The GC can achieve these goals, in part, by replacing paper-based processes with electronic practices that are more modern, faster and easier to use.

The concept of conducting business electronically is nothing new. A number of jurisdictions, including the GC and Canada’s provinces and territories, have developed laws, policies and standards for electronic documents and electronic signatures (e-signatures) since the mid-1990s. These laws:

- rely on internationally recognized rules to create a more certain legal environment for electronic communications and electronic commerce

- recognize that electronic communications should not be denied legal effect simply because they are in electronic form

Whether a signature is paper-based or electronic, the fundamental purpose of the signature is the same. A signature links a person to a document (or transaction) and typically provides evidence of that person’s intent to approve or to be legally bound by its contents. The primary function of a signature is to provide evidence of the signatory’s:

- identity

- intent to sign

- agreement to be bound by the contents of the document

The requirement for a signature can be:

- imposed by an act of Parliament

- imposed by policy

- a customary practice

A signature can be that of a government official or a member of the public (an individual or a business representative).

In the context of the federal government, a signature may be required to:

- express consent, approval, agreement, acceptance or authorization of everyday business activities (for example, to approve a leave request or formally agree to the terms and conditions of a contract)

- emphasize the importance of a transaction or event, or to acknowledge that a transaction or event occurred, such as confirming that a contractor’s bid was received by a deadline

- provide source authentication and data integrity, such as verification that a public health-related notice originated from Health Canada and has not been altered

- certify the contents of a document (that is, a document complies with certain requirements, or a particular process was followed)

- affirm that information contained in a document is true or accurate

- support third-party attestation, such as for an electronic notary function

- support accountability, such as being able to trace individuals to their actions

In some cases, the ability to support e-signatures from more than one individual is required. This requirement can be met in several ways, including through the use of email or a workflow management system.

1.2. Purpose and scope

This document provides guidance on using e-signatures in support of the GC’s day-to-day business activities. It aims to clarify:

- what constitutes an e-signature

- what forms of e-signature are appropriate in the context of the business activity

This document is not intended to be:

- a substitute for legal advice (business owners should always consult with their legal counsel)

- a framework to protect sensitive information from unauthorized disclosure (this document does not address confidentiality requirements)

1.3. Intended audience

This guidance is for GC departments Footnote 1 that are exploring the use of e-signatures in support of their day-to-day business activities.

2. The context of electronic signatures

- In this section

- 2.1 E-signature laws

- 2.2 Determining when an e-signature should be used

- 2.3 Assessing assurance levels

2.1. E-signature laws

Jurisdictions throughout the world have adopted laws that recognize the validity of electronic documents and e-signatures. Although frameworks and definitions vary by jurisdiction, their principles are largely the same. Appendix A lists a number of these sources and their associated definitions.

In Canada, Part 2 of the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act ( PIPEDA ) provides a regime that establishes electronic equivalents to paper-based documents and signatures at the federal level. Part 2 of PIPEDA defines an e-signature as “a signature that consists of one or more letters, characters, numbers or other symbols in digital form incorporated in, attached to or associated with an electronic document.” Essentially, an e-signature can be virtually any form of electronic representation that can be linked or attached to an electronic document or transaction, including:

- user authentication to an internal application to approve something, such as when a supervisor logs into an application to approve a leave request

- using a stylus on a tablet touchscreen to write a signature by hand and capture it in electronic form

- a typed name or signature block in an email

- user authentication to access a website, coupled with a mouse click on some form of acknowledgment button to capture intent

- a scanned hand-written signature on an electronic document

- a sound such as a recorded voice command (for example, a verbal confirmation in response to a question)

There are also some cases where Part 2 of PIPEDA requires the use of a particular class of e-signatures, referred to as a “secure electronic signature.” A secure e-signature is a form of e-signature that is based on asymmetric cryptography. Specific use cases where Part 2 of PIPEDA requires a secure e-signature are:

- documents used as evidence or proof (see PIPEDA Part 2, section 36)

- seals (see PIPEDA Part 2, section 39)

- original documents (see PIPEDA Part 2, section 42)

- statements made under oath (see PIPEDA Part 2, section 44)

- statements declaring truth (see PIPEDA Part 2, section 45)

- witnessed signatures (see PIPEDA Part 2, section 46)

Although Part 2 of PIPEDA set outs clauses for general application, many of the electronic equivalents it outlines are based on an “opt in” framework. Therefore, such provisions do not apply to departments and agencies unless they choose to opt in and list the federal law or provision that includes the signature (or other applicable requirement) to Schedule 2 or Schedule 3 of PIPEDA. Footnote 2

Over the years, rather than choosing to opt in to PIPEDA, several departments and agencies have amended their own statutes to provide clarity regarding e-signatures and electronic documents more generally. For example, Employment and Social Development Canada has addressed this through its:

- Department of Employment and Social Development Act

- Electronic Documents and Electronic Information RegulationsFootnote 3

Related federal regulations (which were enacted before PIPEDA came into effect) are:

- Electronic Payments Regulations, issued pursuant to the Financial Administration Act’s (FAA’s) subsection 10(f)

- Payments and Settlements Requisitioning Regulations, issued pursuant to the FAA’s subsection 10(a) and section 33

Both of these regulations set out a requirement to support digital signatures in association with online electronic transfers. The Secure Electronic Signature Regulations Footnote 4 also uses the term “digital signature” in its definition of a secure e-signature. Therefore, from a technical perspective, a digital signature and a secure e-signature are essentially the same since both:

- are a form of e-signature based on asymmetric cryptography

- rely on public key infrastructure ( PKI ) to manage the associated private signing keys and public verification certificates

However, the Secure Electronic Signature Regulations ( SES Regulations) go further in several respects, including:

- section 2 of the SES Regulations prescribes a specific asymmetric algorithm to support digital signatures

- section 4 of the SES Regulations specifies that the issuing Certification Authority (CA) must be recognized by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat by verifying that the CA has “the capacity to issue digital signature certificates in a secure and reliable manner.” Footnote 5

- section 5 of the SES Regulations includes a presumption that, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, the electronic data has been signed by the person who is identified in the digital signature certificate or who can be identified through that certificate.

2.2. Determining when an e-signature should be used

As mentioned, there are cases where a law (or policy) specifies:

- a requirement for an e-signature

- the type of e-signature required

There are also cases where:

- the legal requirement is only implied

- the need for a signature has been established for some other non-legislative reason

- in either case, the type of e-signature may be unspecified or unclear

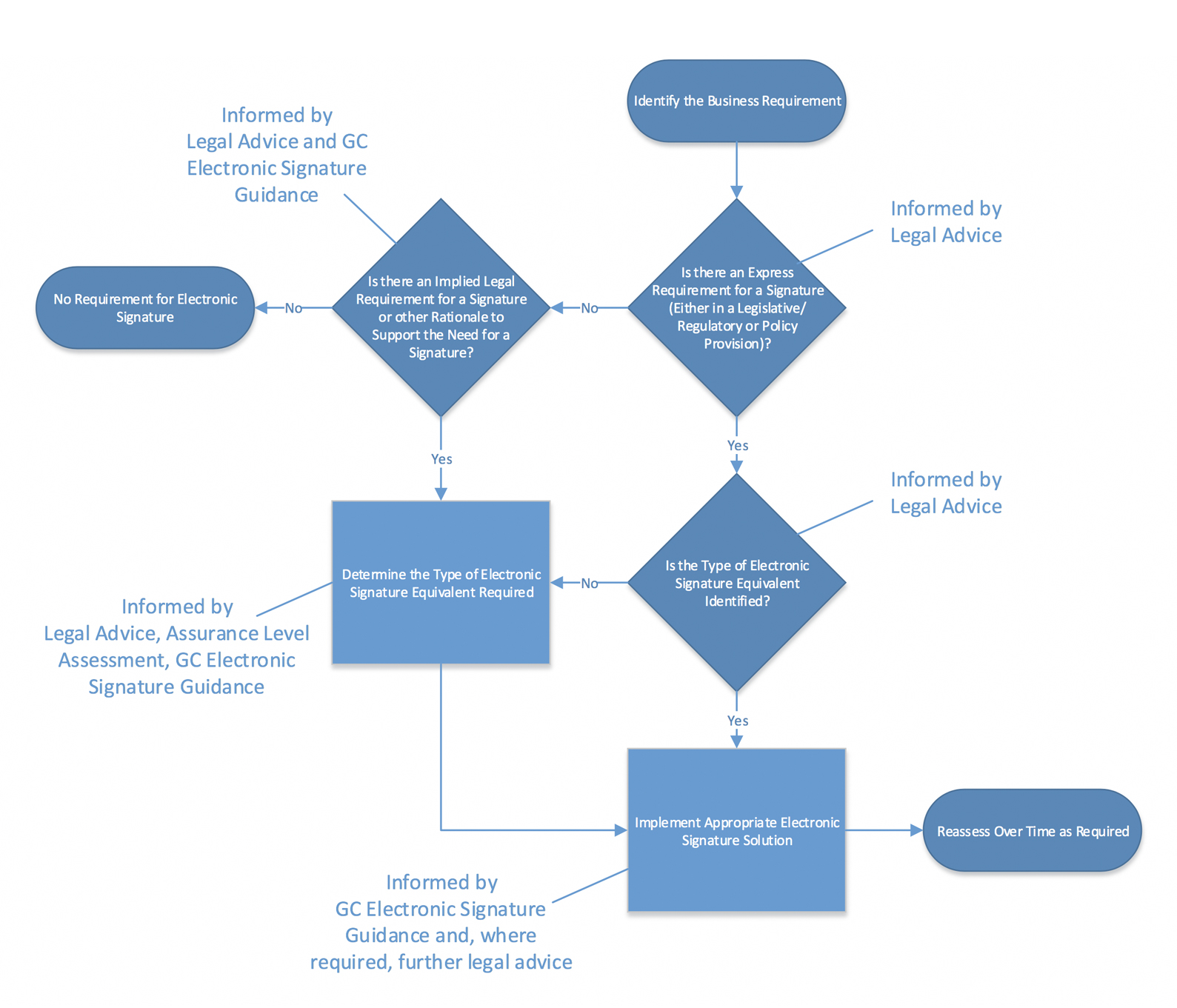

Figure 1 outlines the steps to determine whether an e-signature is required and, if so, what type of e-signature is required. While Figure 1 emphasizes the importance of obtaining legal advice throughout the process, note that the various steps illustrated in Figure 1 will need to be performed in collaboration with other key personnel where appropriate as noted in Annex D. In addition, this document offers guidance on assessing assurance levels (see subsection 2.3), which can be used:

- in the absence of specified legal or policy requirements

- when requirements for implementing an e-signature are not specified or are unclear

2.3. Assessing assurance levels

The Guideline on Defining Authentication Requirements outlines a methodology to determine the minimum assurance level Footnote 6 needed to achieve program objectives, deliver a service or properly execute a transaction.

This methodology can be applied in the context of e-signatures. Footnote 7 An assessment of assurance levels should consider the impact of threats, such as:

- impersonation (the signer is not who they claim to be)

- repudiation (the signer attempts to deny that they originated an e-signature)

- loss of data integrity (the electronic data has been altered since it was signed)

- exceeding authority (the signer is not authorized to sign the associated electronic data)

Once the assessment is complete and the assurance level requirement has been determined, procedural and technical controls can be selected and implemented. Implementation guidance based on each assurance level is provided in Section 3: Guidance on implementing e-signatures.

3. Guidance on implementing e-signatures

- In this section

- 3.1 Considerations for user authentication

- 3.2 Determining the method to be used to implement e-signatures

- 3.3 Supporting information

- 3.4 System and information integrity

- 3.5 Considerations for long-term validation

- 3.6 Using third-party service providers

As mentioned in Section 2, specifics about implementing e-signatures may:

- be required by a law or policy

- be determined as a result of an assurance level assessment and other tools

Depending on the context of the business activity or transaction, implementation considerations can include the following:

- the reason or context for the e-signature is clear (the signature is for approval, agreement, consent, authorization, confirmation, acknowledgment, witness, notarization, certification or other purpose)

- it is clear that the individual(s) understand that they are signing the electronic data (indication of intent to sign)

- the level of authentication is commensurate with the associated assurance level

- the individual(s) have the authority to sign the electronic data

- the method used to establish the e-signature is commensurate with the associated assurance level

- supporting information such as the following is captured, where required:

- date and time that the electronic data was signed

- evidence that the signature was valid at the time it was signed

Note that the requirements associated with each of these areas will vary depending on the assurance level required for the e-signature, as discussed in the following subsections.

3.1. Considerations for user authentication

As noted previously, associating individuals with a signed electronic record is one of the fundamental requirements for an e-signature, and therefore the assurance level of the authentication process and the e-signature are closely coupled. Current GC guidance on authenticating users includes the following:

- Standard on Identity and Credential Assurance, which establishes the four assurance levels associated with identity assurance and credential assurance

- Guideline on Defining Authentication Requirements, which describes a methodology for determining the minimum assurance level needed for user authentication (discussed in subsection 2.3 of this document)

- Guideline on Identity Assurance, which specifies the minimum requirements to establish the identity of an individual for a given level of assurance

- User Authentication Guidance for Information Technology Systems, which provides guidance on selecting security controls for user authentication.

Essentially, the assurance level required for an e-signature dictates the assurance level required for user authentication, which in turn dictates the assurance level required for identity assurance and credential assurance. The guidance documents listed above should be used to determine specific requirements at each assurance level, based on the following recommendations:

- at Assurance Level 1:

- the minimum identity assurance requirements set out in the Guideline on Identity Assurance for Assurance Level 1 must be met

- any of the token types identified in ITSP .030.31: User Authentication Guidance for Information Technology Systems for Assurance Level 1 or higher can be used for user authentication

- the minimum identity assurance requirements set out in the Guideline on Identity Assurance for Assurance Level 2 must be met

- any of the token types identified in ITSP.030.31 for Assurance Level 2 or higher can be used for authentication

- the minimum identity assurance requirements set out in the Guideline on Identity Assurance for Assurance Level 3 must be met

- two-factor authentication is required (refer to Appendix B for additional information)

- the minimum identity assurance requirements set out in the Guideline on Identity Assurance for Assurance Level 4 must be met

- a multi-factor cryptographic hardware device such as a smart card must be used

Additional information on authentication factors and token types associated with user authentication is provided in Appendix B.

3.2. Determining the method to be used to implement e-signatures

Section 2 discussed the various forms of e-signatures. This section sets out the type of e-signature recommended at each assurance level.

Recommendations for e-signatures at each assurance level are as follows:

- at Assurance Level 1, any type of e-signature is acceptable

- at Assurance Level 2, any type of e-signature can be used in conjunction with the authentication requirements for Assurance Level 2 or higher

- at Assurance Level 3, a non-cryptographic e-signature may be used in conjunction with acceptable two-factor authentication, or a digital signature or secure e-signature may be preferred in some circumstances, depending on the target environment and the security controls that are in place

- at Assurance Level 4, a secure e-signature is required in conjunction with a multi-factor cryptographic hardware device

From a technical perspective, an e-signature at a higher assurance level can also be used at lower assurance levels (for example, an Assurance Level 3 e-signature can also be used to support Assurance Level 1 and 2 e-signature requirements). However, other factors such as cost, usability and operational requirements must also be taken into consideration to determine the most sensible approach.

3.3. Supporting information

As discussed in subsection 2.1, an e-signature is any electronic representation where:

- the identity of the individual signing the data can be associated with the electronic data being signed

- the intent of the individual in signing the electronic record is conveyed in some way

- the reason for signing the electronic data is conveyed in some way

There may be requirements to include other supporting information, such as the time that the electronic data was signed.

Supporting information recommended at each assurance level is as follows:

- at Assurance Level 1, supporting information should include:

- the e-signature

- the signed electronic data

- at Assurance Level 2, supporting information should include:

- the authentication method

- the e-signature

- the signed electronic data

- a time-stamp based on standard local system time that indicates the time that the electronic data was signed

- at Assurance Level 3, the supporting information will depend on the type of e-signature:

- for a non-cryptographically based e-signature, supporting information should include the same information as for Assurance Level 2

- for digital signatures or secure e-signatures, the supporting information should include:

- the verification certificate

- the certification path

- associated revocation information or status at the time the electronic data was signed

- is the same as a digital signature or secure e-signature at Assurance Level 3

- must also include a secure time-stamp Footnote 8

Other supporting information may also be required in order to meet specific business needs.

3.4. System and information integrity

System and information integrity is another key factor that applies to:

- the original signed electronic data

- the e-signature

- any other supporting information that may be associated with the electronic transaction (discussed in subsection 3.3 of this document)

In addition, the integrity of the association between all of these elements must remain intact over time. Some of these elements may be captured and protected in different ways, including the use of system audit logs and, or as part of, the digital signature or secure e-signature. All the supporting information, regardless of where or how it is stored, is collectively referred to as the transaction record.

It is expected that certain system and information integrity security controls will be in place to protect the integrity of:

- the electronic transactions

- the transaction records

ITSG-33, Annex 1, defines three integrity levels: low, medium and high. This document anticipates that GC systems and information will be protected at the medium integrity level. The profile of Protected B, medium integrity and medium availability, defined in ITSG-33, Annex 4A, Profile 1, should be consulted to determine the minimum security controls that should be in place, particularly with respect to the following security control families:

- access control (AC)

- audit and accountability (AU)

- identity and authentication (IA)

- system and information integrity (SI)

Recommendations for integrity requirements at each assurance level are as follows:

- at Assurance Level 1, medium integrity applies; however, there is no requirement to maintain or retain transaction records

- at Assurance Level 2:

- medium integrity applies to the electronic transaction and the transaction record

- the transaction record should be retained as stipulated for Assurance Level 2 in ITSP.30.031 (see Table 9, Records Retention column) or by applicable legislation, policy or business requirement

- medium integrity applies to the electronic transaction and transaction record

- when using a digital signature or secure e-signature, at least some of the integrity requirements will be supported by the signature itself, including the integrity of the signed electronic data

- algorithms and associated key lengths approved by the Canadian Security Establishment ( CSE ) must be used as stipulated in ITSP.40.111

- any supporting elements that are not explicitly integrity-protected by the digital signature or secure e-signature must be captured in an audit log

- transaction records should be retained as stipulated for Assurance Level 3 in ITSP.30.031 (see Table 9, Records Retention column) or by applicable legislation, policy or business requirement

- the secure e-signature applied by the individual signing the electronic data protects the electronic data being signed, and a combination of factors protects the signature process itself

- a secure time-stamp is required and may be provided by a trusted third party

- CSE-approved algorithms and associated key lengths must be used as stipulated in ITSP.40.111

- transaction records should be retained as stipulated for Assurance Level 4 in ITSP.30.031 (see Table 9, Records Retention column) or by applicable legislation, policy or business requirement

3.5. Considerations for long-term validation

For non-cryptographic e-signatures, all the information necessary to validate the signature is expected to be available for as long as the record needs to be retained. The e-signature must be able to be verified and confirmed over time.

For a digital signature or secure e-signature, there are a number of steps to ensure that the signing operation is performed with legitimate credentials at the time the electronic record is signed. These steps include verifying that the public key certificate that corresponds to the private signing key:

- is within its specified validity period

- has not been revoked

- successfully chains to a recognized trust anchor

However, over time, some aspects of validation that were in place when the electronic record was signed may change. For example, the public key certificate may expire, or it may be revoked. In addition, advancements in cryptography and computing capabilities may make a cryptographic algorithm (or the associated key length) used to perform the signing operation vulnerable at some point in the future.

This is where the concept of long-term validation ( LTV ) becomes important. Because circumstances will change over time, it is important to cryptographically bind certain information to the originally signed electronic document or record. Such information includes:

- the time at which the electronic document or record was signed

- the public key certificate(s) required to verify the signature

- the associated certificate revocation status information at the time the electronic record was signed

The procedure for LTV can be recursive to accommodate changes in circumstances over a long period so that the originally signed electronic document or record can be verified for many years or even decades. Technical specifications have been developed to support LTV based on the format or syntax of the electronic document or record as follows:

- the Portable Document Format Advanced Electronic Signature ( PAdES ) standards

- the eXtensible Markup Language Advanced Electronic Signature ( XAdES ) standards

- the Cryptographic Message Syntax Advanced Electronic Signature ( CAdES ) standards

Another consideration is a change to the format of the original electronic data document or record, such as when it is converted for long-term archiving. Changing the format will render the original digital signature or secure e-signature invalid, as the embedded data integrity check will fail. In fact, the signature may be removed altogether because of the conversion. In some cases, it may be possible to create a new digital signature or secure e-signature (for example, by using a trusted source to verify that the converted content was originally signed by a specific individual at a certain time). Another possible solution is to adopt standards that are specifically designed to address LTV issues, such as PDF /A-2. However, such options may not be possible in all circumstances, and there may need to be another solution such as retaining metadata that indicates the circumstances under which the original content was signed (such as who signed it, when it was signed, etc.).

Although expected to be extremely rare, there may be cases where a public key certificate is revoked with the invalidity date and time set to sometime in the past. This could be due to several reasons, including discovering that the private signing key had been compromised but the compromise was not detected until some point in the future. This could mean that a digital signature or secure e-signature that was thought to be valid at the time it was created is actually invalid, as the certificate status should have been revoked at the time the electronic document or record was signed. In this case, procedural steps (which are outside the scope of this document) must be taken to determine whether the signature was created by the claimed individual and under the appropriate circumstances.

3.6. Using third-party service providers

Third-party service providers offer various forms of e-signature services that the GC can use, under appropriate circumstances. Business owners must assess whether a third-party service can be used based on:

- specific business requirements

- associated minimum assurance levels

In addition, third-party solutions should be based on industry-accepted standards. Proprietary solutions should be avoided wherever possible to prevent vendor lock-in and to promote interoperability.

There are a number of reasons that services provided by third parties may be considered. For example, a third-party vendor may offer a suitable workflow product that meets the needs of the department (that is, it supports a given business requirement and meets the e-signature and audit requirements). Another example is where a cloud service provider offers acceptable e-signature capabilities to support a GC application hosted in the cloud.

Another consideration is when the GC is interacting with external businesses and individuals. Digital signatures created by the GC need to be verified by these external entities, and therefore it will be necessary to use certificates that have been issued by CAs that are recognized external to the GC. Footnote 9 There may also be circumstances where a digital signature is generated by an external entity that will also need to be recognized by the GC.

4. Summary

This document aims to clarify the interpretation and implementation practices for using e-signatures. Its goal is to provide cost-effective and sensible solutions that enhance the user experience and reduce the time required to conduct day-to-day business activities where e-signatures can be applied in place of paper-based approaches.

Table 2 summarizes the recommendations provided in section 3 of this document at each assurance level for:

- the minimum acceptable type of e-signature

- levels of authentication

- time-stamp requirements

- supporting information recommended at each assurance level

- system and information integrity requirements

- transaction record retention periods

Table 2 Notes

Table 2 Note 1The choice of the specific e signature method and associated implementation requirements suggested at this level (as identified in this row) are to be determined by the business owner. Additional risk mitigation measures may be required for non-cryptographic e signatures at Assurance Level 3. If a PKI-based soft token is used to support the e signature requirement, the authentication process must be complemented with an appropriate second authentication token.

A multi-factor hardware cryptographic device must be used at this assurance level. Although a multi-factor one-time-password device meets the authentication requirements for Assurance Level 4, it does not have the necessary functionality to support a secure e-signature.

Determined by type:

- for non-cryptographic e-signature, include authentication method, ES, signed electronic data, time-stamp

- for cryptographic e-signature, add verification certificate and certification path and associated revocation information

Appendix A: sources and definitions related to e-signatures

This Appendix lists sources of information from national and international jurisdictions that address e-signatures. Definitions of terms used in these sources are also summarized.

This information is used to help establish the basic concepts behind e-signatures outlined in this document. Sources from non-Canadian jurisdictions are included in order to:

- demonstrate the breadth of coverage

- highlight terminology used in other jurisdictions, which is particularly useful where interoperability with other jurisdictions may be required

Canadian federal acts and regulations that address e-signatures include:

- Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA), Part 2 ( PDF , 542 KB)

- Secure Electronic Signature Regulations (annexed to PIPEDA and the Canada Evidence Act) ( PDF , 147 KB)

- Electronic Payments Regulations (annexed to the Financial Administration Act (FAA)) ( PDF , 177 KB)

- Payments and Settlements Requisitioning Regulations (annexed to the FAA) ( PDF , 202 KB)

In addition, there are over 20 federal acts and almost 30 regulations listed on the Department of Justice Canada website that include references to “electronic signature.” Footnote 10

Most Canadian provincial and territorial jurisdictions have enacted electronic commerce and transaction laws that provide electronic equivalents to paper-based signatures, along with other requirements, by adopting the principles established in the Uniform Law Conference of Canada’s model law (the Uniform Electronic Commerce Act ( UECA )). Footnote 11 The UECA is technology-neutral and defines an “electronic signature” as electronic information that a person creates or adopts in order to sign a record and that is attached to, or associated with, the record. An e-signature, defined in this way, functions as a signature in law. As stated in the UECA guide, the act itself does not set any technical standard for the production of a valid signature. As a result, e-signatures can be constituted in a number of ways unless rules dictate otherwise. Footnote 12

Non-Canadian sources of interest that address terms and concepts related to e-signatures include:

- the US Uniform Electronic Transaction Act ( UETA ) ( PDF , xx KB)

- the US Electronic Signatures in Global and National Commerce Act (E-SIGN) ( PDF , 223 KB)

- the European Union (EU) Electronic Identification, Authentication and Trust Services ( eIDAS) Regulation

- the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law ( UNCITRAL ) Model Law on Electronic Signatures ( PDF , 249 KB)

Specific terms defined in these sources include the following (see Table A1):

- e-signature

- secure e-signature

- digital signature

- advanced e-signature ( AdES )

- qualified e-signature ( QES )

PIPEDA Part 2, Sections 31(1), 48(1) and 48(2) collectively define a “secure electronic signature” as “an electronic signature that results from the application of a technology or process…” with the following characteristics:

- “the electronic signature resulting from the use by a person of the technology or process is unique to the person;

- the use of the technology or process by a person to incorporate, attach or associate the person’s electronic signature to an electronic document is under the sole control of the person;

- the technology or process can be used to identify the person using the technology or process; and

- the electronic signature can be linked with an electronic document in such a way that it can be used to determine whether the electronic document has been changed since the electronic signature was incorporated in, attached to or associated with the electronic document.”

“a secure electronic signature in respect of data contained in an electronic document is a digital signature that results from completion of the following consecutive operations:

- application of the hash function to the data to generate a message digest;

- application of a private key to encrypt the message digest;

- incorporation in, attachment to, or association with the electronic document of the encrypted message digest;

- transmission of the electronic document and encrypted message digest together with either

- a digital signature certificate, or

- a means of access to a digital signature certificate; and

- after receipt of the electronic document, the encrypted message digest and the digital signature certificate or the means of access to the digital signature certificate,

- application of the public key contained in the digital signature certificate to decrypt the encrypted message digest and produce the message digest referred to in paragraph (a),

- application of the hash function to the data contained in the electronic document to generate a new message digest,

- verification that, on comparison, the message digests referred to in paragraph (a) and subparagraph (ii) are identical, and

- verification that the digital signature certificate is valid in accordance with section 3 (of the SES Regulations).”

“the result of the transformation of a message by means of a cryptosystem using keys such that a person having the initial message can determine:

- whether the transformation was created using the key that corresponds to the signer’s key, and

- whether the message has been altered since the transformation was made.”

Although the UNCITRAL Model Law on Electronic Signatures ( PDF , 249 KB) does not provide an explicit definition, it also uses the term “digital signature,” consistent with the PIPEDA Part 2 definition.

The definitions provided in Table A1 lead to these observations:

- Although there are numerous definitions for “electronic signature,” the intent behind each is essentially the same.

- From a technical perspective, the terms “secure electronic signature,” “digital signature,” “AdES” and “QES” are essentially equivalent. They are all based on asymmetric cryptography and rely on public key infrastructure (PKI) to manage the associated keys and certificates. However:

- there are specific requirements in the SES Regulations that apply to the term “secure electronic signature”

- there are also more stringent implementation requirements associated with a QES

It should also be noted that the description provided in the SES Regulations is so granular that it actually prescribes a specific digital signature algorithm. Footnote 13 Whether this was intentional (to promote interoperability) or not (it was assumed at the time that all digital signature algorithms have the same mathematical properties) is unclear. In any case, ITSP.40.111 should be consulted for approved algorithms and associated key lengths.

Appendix B: user authentication factors and token types

The purpose of this Appendix is to help clarify which authentication token types described in ITSP.30.031 can be used at each assurance level. Although ITSP.30.031 should be consulted for additional details, some of the basic concepts associated with authentication factors and tokens are provided here for the convenience of the reader.

Fundamentally, authentication factors are described as:

- something the user knows

- something the user has

- something the user is

Token types for “something the user knows” include:

- memorized secret tokens (a password associated with an account or user ID)

- pre-registered knowledge tokens (for example, pre-established answers to a set of challenge questions)

Token types for “something the user has” include:

- look-up secret tokens (static grid or “bingo” cards)

- out-of-band tokens (a push notification to an out-of-band device such as a smart phone)

- single-factor one-time-password (OTP) devices (an Open Authentication (OATH) token)

- single-factor cryptographic device (a USB key with built-in cryptographic capabilities and secure key storage)

“Something you are” token types include biometrics such as a fingerprint, retinal scan and facial recognition. However, in accordance with ITSP.30.031, biometrics can be used only in a multi-factor authentication scenario, such as using a fingerprint scan to unlock a hardware token. Footnote 14

Multi-factor tokens include:

- multi-factor OTP devices, such as an OTP device that requires local user authentication before displaying the passcode

- multi-factor hardware cryptographic devices, such as a smart card Footnote 15

Multi-factor authentication (or, more specifically, two-factor authentication) can also be achieved by combining an appropriate “something you know” token with an appropriate “something you have” token. Recommendations for acceptable two-factor solutions are provided in Recommendations for Two-Factor User Authentication Within the Government of Canada Enterprise Domain.

Table B1 summarizes acceptable token types at each assurance level.

Table B1 Notes

Table B1 Note 1A memorized secret is typically a password associated with a specific user ID. The difference between an Assurance Level 1 memorized secret and an Assurance Level 2 memorized secret lies in the strength of the password. A password must meet minimum strength and entropy requirements before it can be considered sufficient for an Assurance Level 2 memorized secret. Refer to Annex B in ITSP.30.031 for additional information.

Table B1 Note 2

As noted above, an appropriate combination of two Assurance Level 2 tokens can also be used to achieve the equivalent of an Assurance Level 3 token, as specified in ITSP.30.031. For example, an Assurance Level 2 memorized secret token used in combination with an appropriate out-of-band token (such as a “push notification” to a GC-managed smart phone) is equivalent to an Assurance Level 3 token and therefore could be used in tandem to support e-signatures at Assurance Level 3.

Table B1 Note 3

A multi-factor OTP device is sufficient for Assurance Level 4 authentication; however, it does not have the necessary functionality to generate a digital signature or secure e-signature, which is mandatory at Assurance Level 4.

Appendix C: examples of business activities

The purpose of this Appendix is to provide examples of the types of business activities that may correspond to each assurance level. In general, as the importance and/or value of the business activity increases, so does the associated assurance level. However, it should be noted that the business activity examples provided here are for illustrative purposes only and in no way are meant to be prescriptive.

Individual departments should perform their own assessments in the context of their business needs and requirements. The overall objective should be to:

- leverage existing investments where feasible (departments should use what they already have where it makes sense)

- enhance the user experience

- implement cost-effective, sensible solutions commensurate with the assessed assurance level

- Online financial transactions where existing legislation requires a digital signature or secure e-signature (for example, Electronic Payments Regulations and Payment and Settlements Requisitioning Regulations)

- PIPEDA Part 2 use cases where applicable

- Binding contracts with external entities that exceed a certain dollar value (based on risk tolerance as determined by departmental evaluation)

- Managerial approvals of financial transactions that do not require a digital signature or secure e-signature (for example, approval of employee expense claims)

- Binding contracts with external entities that are below a certain dollar value (based on risk tolerance as determined by departmental evaluation)

- One or more of the business activity examples provided below under Assurance Level 2 may apply here (risk tolerance varies by department; some departments may elect to implement more stringent security controls for some of the business activities identified below under Assurance Level 2)

- Leave submission and approvals

- Travel requests and approvals

- Time sheet submissions and approvals

- Expense claim submissions (but not approvals)

- Online submission of certain applications or forms from external users

- Intradepartmental memoranda of understanding

- Everyday correspondence with little to no implied commitment on behalf of the sender or the GC

Appendix D: guidance sent to DSOs via e-mail on 18 September 2017

(Note that titles and links to some of the referenced source documentation have been updated to reflect the most recent versions available.)

The following guidance on the use of electronic signatures for security screening is being provided in response to discussions at the Government of Canada Security Council (GCSC) and it was felt that it would be beneficial to all DSOs.

The objective of obtaining an individual’s signature on security screening forms is to confirm that they acknowledge that they have been informed that their personal information will be collected and to obtain their consent that their personal information will be disclosed for security screening purposes (as outlined in Privacy and Consent clauses), and to comply with sections 7 and 8 of the Privacy Act. It is also important to demonstrate that the person intends to be bound to the obligations attached to that signature.

On the security screening form, a signature does not need to be in a particular form to be legally binding and serves the same purpose whether it is “wet” or electronic. A wet signature is created when an individual marks a document with their name using ink which requires time to dry. An electronic signature is defined within the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) as “consisting of one or more letters, characters, numbers or other symbols, in digital form, incorporated in, attached to or associated with an electronic document.”

Departments and agencies wanting to pursue the use of electronic signatures as an alternative to the traditional wet signature should consider the following to help determine whether such a move is viable in their operating environment and to be positioned to mitigate any potential legal risk which may arise.

- The implementation of electronic signatures within a department or agency should be done in collaboration with IT and business stakeholders (where appropriate), and, when appropriate, departmental legal counsel may be consulted for advice

- The type of technology to be used and approach to implementation should align with the Government of Canada Strategic Plan for Information Management and Information Technology 2017-2021.

- Privacy and consent clauses should be the same as those used in the paper forms to ensure that there was no discrepancy between the two formats.

- The underlying process and standard operating procedures related to the collection, receipt and storage of electronic documents and related signatures would need to be documented and consistently implemented.

- Should the use of an electronic signature ever be challenged in court, the department or agency would need to be able to demonstrate the reliability of the system/technology and underlying processes and procedures and provide evidence that at all material times the IT system(s) / device(s) used were operating properly or, if not, there are no other reasonable grounds to doubt the integrity of the electronic signature.

For additional guidance, you may want to refer to the Canadian General Standard Board’s standard entitled Electronic Records as Documentary Evidence which provides information and guidance for developing policies, procedures, processes and documentation that support the reliability, accuracy and authenticity of electronic records. Additionally, the Directive on Identity Management and Standard on Identity and Credential Assurance provide guidance with respect to validating the identity of individuals which apply equally to the use of electronic signatures.

We trust this is of assistance. Please address any inquiries to SEC@tbs-sct.gc.ca.

Best regards,

Rita Whittle

Director General, Security and Identity Management Policy, Chief Information Officer Branch

Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat / Government of Canada

Rita.Whittle@tbs-sct.gc.ca / Tel: 613-369-9683 / TTY: 613-369-9371Footnotes

Footnote 1Throughout this document, “departments” denotes federal departments and agencies.

An exception to the opt in requirement is section 36 of PIPEDA.

Currently, there are over 20 federal acts and almost 30 regulations listed on the Department of Justice Canada website that include references to “electronic signature” (based on a search for the term “electronic signature” using the Department of Justice Canada advanced search tool).

The Secure Electronic Signature Regulations are annexed to both PIPEDA and the Canada Evidence Act.

Both the algorithm description and the recognition process are currently under review.

Note that assurance levels should not be confused with levels of authority.

Note that other tools such as the ITSG 33: Security Categorization Guide may also be used to assist in the assessment process.

A secure time-stamp is obtained from a trusted source. The integrity of the secure time-stamp is cryptographically protected.

Note that electronic signatures created using certificates issued by internal GC CAs such as the Internal Credential Management (ICM) CA are typically not capable of supporting interaction with external entities, as the issuing CA is not a recognized trust anchor outside the GC. (There are a limited number of exceptions where ICM issues certificates to external entities, but such exceptions do not offer a viable long-term solution.)

Based on a search for the term “electronic signature” using the Department of Justice Canada advanced search tool.

Signature electronic equivalents found in provincial and territorial electronic transaction laws do not apply to the GC.

The UECA states that authorities responsible for the legal signature requirement can make regulations where it is felt that the situation implies a degree of reliability of identification or association with the document to be signed. Similarly, signatures submitted to government (provincial and territorial) must conform to information technology requirements and to any rules on the method of making them or their reliability. See the Uniform Law Conference of Canada’s discussion of the Uniform Electronic Commerce Act.

The properties identified in the SES Regulations describe a digital signature based on the Rivet, Shamir, Adleman (RSA) algorithm. Other digital signature algorithms such as the Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA) are also valid but have different mathematical properties that do not precisely conform to the description from the SES Regulations.

As advancements in biometric technology continue to be made, this restriction may be revisited.

Note that multi-factor software cryptographic token (for example, a PKI-based soft token such as a myKEY soft token) is purposely omitted here because it is not considered to be an adequate multi-factor solution according to the guidance provided in ITSP.30.031. Furthermore, PKI-based soft tokens are not sufficient at Assurance Level 3 unless the authentication process is coupled with another appropriate Assurance Level 2 token (which is typically not supported with existing GC deployments).